“Compounding is the process in which an asset’s earnings, from either capital gains or interest, are reinvested to generate additional earnings over time. This growth, calculated using exponential functions, occurs because the investment will generate earnings from both its initial principal and the accumulated earnings from preceding periods. Compounding, therefore, differs from linear growth, where only the principal earns interest each period.” (Investopedia)

John Kotter, in the final chapter of his famous book on change management Leading Change, applies the concept of compounding to people’s development of leadership and other skills.

Kotter gives an hypothetical example:

Between age thirty and fifty, Fran “grows” at the rate of 6 percent — that is every year she expands her career-relevant skills and knowledge by 6 percent. Her twin sister, Janice, has exactly the same intelligence, skills, and information at age thirty, but during the next twenty years she grows at only 1 percent per year… How much difference will this relatively small learning differential make by age fifty?

The difference between a 6 percent and a 1 percent growth rate over twenty year is huge. If they each have 100 units of career-related capability at age thirty, twenty years later, Janice will have 122 units, while Fran will have 321. Peers at age thirty, the two will be in totally different leagues at age fifty. (Leading Change, p. 181)

Clearly no two people are identical in real life, so the starting point of Janice and Fran couldn’t be perfectly equal, but the idea expressed by Kotter is clear. A little difference in “personal growth rate” over a long period of time will end up creating huge differences in people’s skill and chances to succeed.

While it is obviously impossible to measure it in practice, the idea that different “personal growth rates” accumulate through life, giving some people advantage over others, it is a fact of life.

This idea of personal compound growth and the consequence it has on people’s life reminds me also of a scripture in the Book of Doctrine & Covenants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Doctrine & Covenants 130:19 we read:

And if a person gains more knowledge and intelligence in this life through his diligence and obedience than another, he will have so much the advantage in the world to come.

Lifelong Learning

Lifelong learning is an essential element of “compounded growth”. Lifelong learning is the driver of personal and societal change and improvement. For individuals, lifelong learning is the key not only to ensuring continued employability but also to personal well-being and self-fulfillment. For broader society, lifelong learning can be an important factor in finding solutions to difficult challenges.

Lifelong learners are motivated to learn and develop because they want to: it is a deliberate and voluntary act, and it has become an absolute necessity in our modern society.

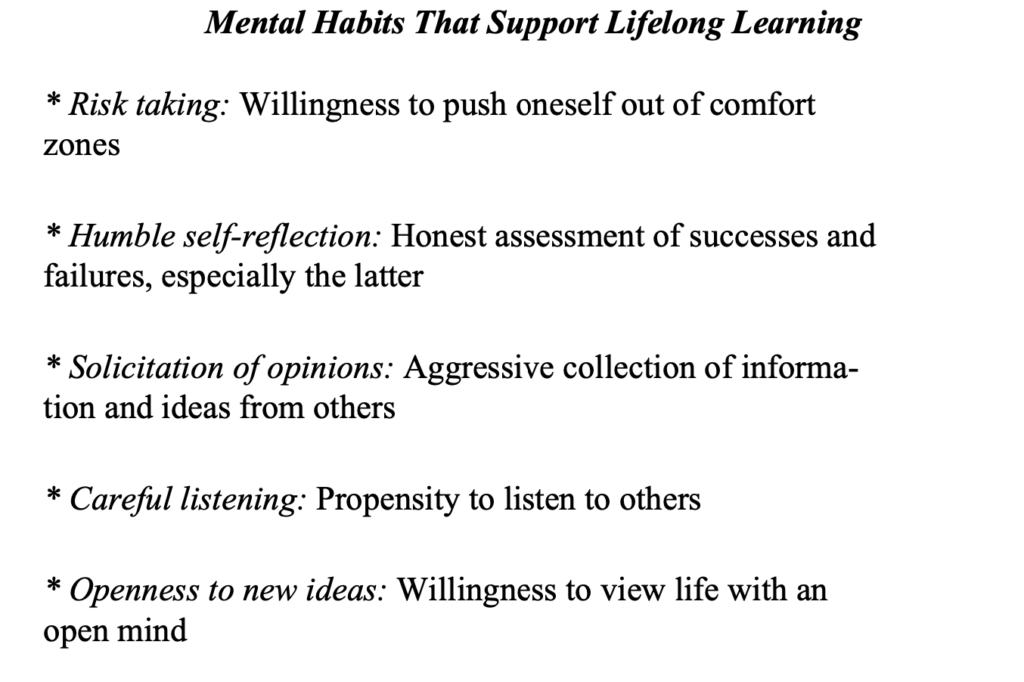

Kotter lists four mental habits that support lifelong learning. Lifelong learning requires more risk taking, humble self-reflection, solicitation of opinion, and careful listening.

“Lifelong learners take risk. Much more than others, these men and women push themselves out of their comfort zone and try new ideas. While most of us become set in our ways, they keep experimenting.

Risk taking inevitably produces both bigger successes and bigger failures. Much more than most of us, lifelong learners humbly and honestly reflect on their experiences to educate themselves. They don’t sweep failure under the rug or examine it from a defensive position that undermine their ability to make rational conclusions.

Lifelong learners actively solicit opinions and ideas from others. They don’t make the assumptions that they know it all or that most other people have little to contribute. Just the opposite, they believe that with the right approach, they can learn from anyone under almost any circumstance.

Much more that the average person, lifelong learners also listen carefully, and they do so with an open mind. They don’t assume that listening will produce big ideas or important information very often. quite the contrary. But they know that careful listening will help give them accurate feedback on the effect of their actions. And without honest feedback, learning becomes almost impossible (Leading Change, p. 182)

Great leaders are lifelong learners

In 1562, an 87-year-old Michelangelo expressed the essence of the idea of lifelong learning when he inscribed the words Ancaro Impari (“I’m still learning”) on a sketch he was developing.

Many successful people and leaders, in particular, seem to read more than almost anyone else. Lincoln was famous for reading both the Bible and Shakespeare; Franklin Roosevelt loved Kipling.

According to an HBR article, “Nike founder Phil Knight so reveres his library that in it you have to take off your shoes and bow.”

Warren Buffett spends five to six hours a day reading five newspapers and 500 pages of corporate reports. “Read 500 pages like this every day,” said Buffett. “That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest. All of you can do it, but I guarantee not many of you will do it.”

Bill Gates reads 50 books a year.

Mark Zuckerberg aimed to read at least one book every two weeks.

Elon Musk grew up reading two books a day, according to his brother.

Oprah Winfrey credits books with much of her success: “Books were my path to personal freedom.”